The more I learn about racism, the more I realize how hard it is to argue against racist ideas. It’s not hard to oppose them, but it’s hard to say something that will get the other person to at least stop and think, let alone change their mind. This week I read Reni Eddo-Lodge’s Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People About Race. A lot of the ideas below were triggered by the excellent explanations and sometimes painful truths in the book.

I try to find a balance between consuming new ideas and staying informed and getting depressed from seeing too much hatred and ignorance online. It’s a thin line to walk on and I often get it wrong. Some of the discourse online scares the hell out of me. A good example is an article on a Dutch news site about the unmarked order troops in Portland who pick up protestors from the streets without identifying themselves and take them away in unmarked rental vans. The comments below that article are filled with remarks that what these troops are doing is justified and that the BLM protests and “Antifa” pose a serious threat to these cities and communities. After all, Trump declared that Antifa is a terrorist organization.

Antifa stands for anti-fascist. A definition of fascism is “a political philosophy, movement, or regime that exalts nation and often race above the individual and that stands for a centralized autocratic government headed by a dictatorial leader, severe economic and social regimentation, and forcible suppression of opposition”. The word was originally used for Mussolini’s party and has since been generalized to include those with similar believes. Against that background and definition, I consider myself to be Antifa. I hope and even assume that most people commenting on the article would not identify as fascists even if some might not identify as explicitly anti-fascist.

Moving away from this specific example, how do you explain to someone who feels picking up BLM protestors of the street is good and just that black people have to deal with systemic and unjust racism and that they are right to demand structural changes? I don’t think many people who aren’t sympathetic towards the BLM organization and protests are afraid of losing their white privilege at this point. I think in many cases they are just scared of change in general. They want things to go back to “normal”. Where normal means that everyone accepts the world that we have today, inequalities and injustices and all. I think. Maybe?

The push for quiet and complacency isn’t new. In 1963 Liberation Magazine published an article by Martin Luther King, Jr that included the following statement: ‘First, I must confess that over the last few years I have been gravely disappointed with the white moderate. I have almost reached the regrettable conclusion that the Negro’s great stumbling block in the stride toward freedom is not the White Citizen’s Counciler or the Ku Klux Klanner, but the white moderate who is more devoted to “order” than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice; who constantly says “I agree with you in the goal you seek, but I can’t agree with your methods of direct action”; who paternalistically feels he can set the timetable for another man’s freedom; who lives by the myth of time and who constantly advises the Negro to wait until a “more convenient season.” ‘Shallow understanding from people of goodwill is more frustrating than absolute misunderstanding from people of ill will. Lukewarm acceptance is much more bewildering than outright rejection.’

I’m ashamed to say that I don’t think we’ve made much progress in this area since 1963. That’s 57 years and two generations! Can you blame black people for getting frustrated with a society, government, and white people from both the left and the right not caring enough to make some real changes?

Part of the challenge of making society less racist is that the changes can’t be made by black people. Racism is about power. It’s about being a position to negatively impact other people’s lives. Lasting changes will have to be made by those in power. Unfortunately, those at the top also benefit the most from the current racist, misogynist power structures and thus have the most to lose. They will only change things when they are forced to. In places where quotas about the number or percentage of women that are being hired or women that are part of boards and leadership teams are enforced the number of (white) women is increasing.

Going forward we don’t just need quota on the number of women, we also need quota on the number of black people that are being hired and that are being promoted into leadership positions.

Many oppose quotas, stating that “the best person for the job” should be hired. But if you think that the homogeneous flock of middle-aged white men currently clogging the upper echelons of most professions got there purely through talent and hard work you’re fooling yourself. We don’t live in a meritocracy, and to pretend that simple hard work will allow people of all skin colors, genders, religions, etc. to achieve the same level of success is an exercise in willful ignorance.

To change racist laws and regulations we need a different approach as no institution can force a government to make changes. Keeping the status quo needs to lead to a structural loss of power or money to enforce changes. This could be achieved if the protests last long enough and through means like the broadly supported bus strike in Montgomery, Alabama between 1955 and 1956. It can also be achieved if those demanding change get so much support that not meeting demands means losing elections.

Even if you’re not keen on protesting you can contribute to the push for a more just world from the comfort of your own home. Especially if you are white. You can help spread the call for change to racist laws and institutions on social media, through letters to newspapers and among your friends and family. People who are not racist, but even people who are anti-racist are often moderate and polite about the issue.

The far-right don’t hold themselves to the same standards. They use bold claims, fear-mongering, and often lies. They use all the platforms they have access to, regardless of whether that’s a “decent” thing to do. They reach a lot of people with these tactics and speak to fear, which is a powerful tool. Their sympathizers don’t nod passionately at their screen when they read these lies, they amplify these right-wing voices in all the ways they have available to them. And they don’t fight among themselves even if they might not agree on all the nitty-gritty right-wing details.

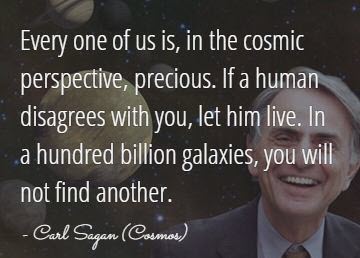

We need to do the same. We need to share our passion for equality and anti-racism with the world. It’s uncomfortable and it might mean we end up in the occasional online shitstorm, but agreeing quietly at home isn’t helpful at this point. To weather the shit storms and limit the number of storms we need to also form a left-wing, anti-racist front. We are too happy to shout at people whose opinion is slightly different from ours while we avoid engaging with people who have a wildly different opinion. Let’s suspend our internal disagreements. They are, frankly, not relevant at the moment. We have bigger fish to fry.

Let’s agree to work together for now and amplify the voices of minorities. The mess we are living in was created by people, it can be dismantled by people, and it can be rebuilt in a way that serves all, rather than a small hoarding few. It won’t be easy but we have to keep working at it. And just as important: we have to continue to believe that we can achieve real change. Because if we lose hope they win and we’re f*cked.